Most Western Christian groups use mechanical instruments as part of their singing and praise to God. Yet it is virtually uncontroverted that early Christians sang without the accompaniment of such instruments. While many may enjoy the sounds and most may accept the use of pianos, drums, guitars, and the like without substantial question, every major group of Bible translators agrees with the lexicographers regarding the Greek words translated “sing” in the New Testament. All major translations render the Greek verbs “sing.” If the word meant something more, like “sing and play a mechanical instrument,” for instance, some teams of scholars would surely translate them that way.

In addition, historians agree that mechanical instruments were not used in Christian worship for hundreds of years after the church began. According to The Catholic Encyclopedia, “For almost a thousand years Gregorian chant, without any instrumental or harmonic addition, was the only music used in connection with the liturgy. The organ, in its primitive and rude form, was the first, and for a long time the sole, instrument used to accompany the chant.” When mechanical instruments were first introduced in Christian worship, they were not readily accepted. According to The Oxford History of Christian Worship, “Only during the high and late Middle Ages (1100–1450) did any instrumental musicians gain a significant liturgical role.”[1] The Catholic Encyclopedia agrees that, “At all events, a strong objection to the organ in church service remained pretty general down to the twelfth century.”

It is also noteworthy that many influential theologians did not believe the New Testament authorizes the use of mechanical instruments. For example, Thomas Aquinas, a prominent Catholic theologian who lived during the mid-13th century, is quoted as having said, “Our Church does not use musical instruments, as harps and psalteries, to praise God withal, that she may not seem to Judaize.” Similarly, Charles H. Spurgeon, recognized as one of the greatest Baptist preachers, preached for more than thirty years in the late 19th century to thousands of people in the Metropolitan Baptist Tabernacle in London, England, and never had mechanical instruments in worship assemblies.

John Calvin, the founder of the Presbyterian Church, explicitly condemned the use of musical instruments in worship, claiming, “Men who are fond of outward pomp may delight in that noise; but the simplicity which God recommends to us by the apostle is far more pleasing to him.” Adam Clarke, a noted Methodist preacher in the late 1700-early 1800's, also protested, “Music, as a science, I esteem and admire: but instruments of music in the house of God I abominate and abhor. This is the abuse of music; and here I register my protest against all such corruptions in the worship of the Author of Christianity.”

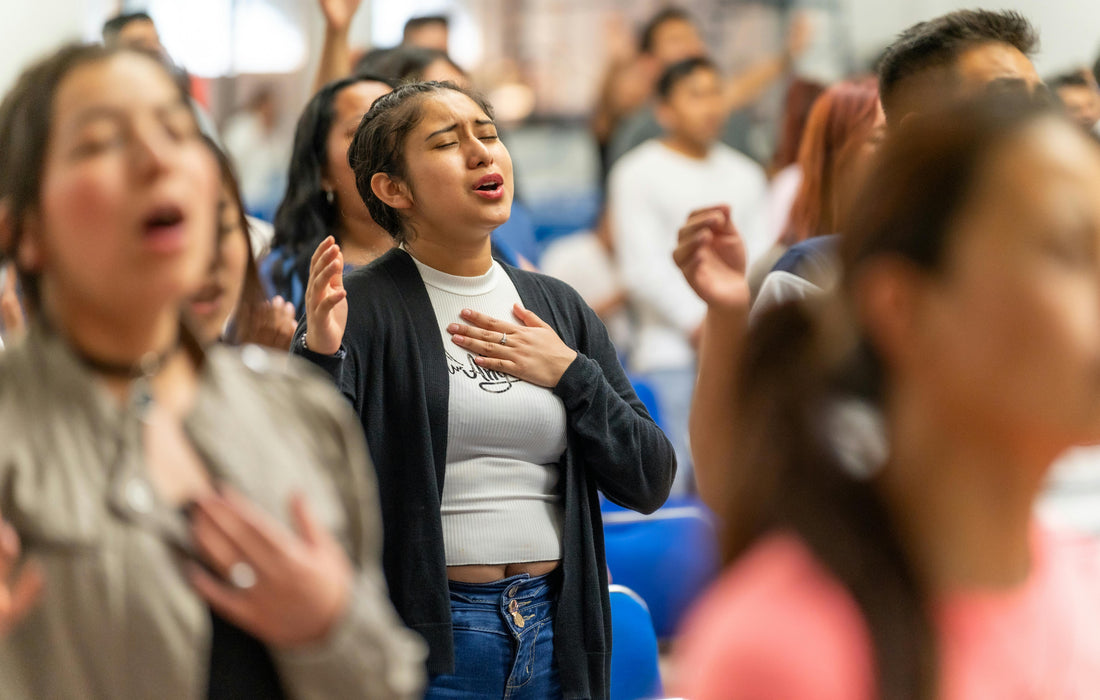

It is easy to see why a capella, which literally means “in the style of the chapel or choir,” refers to music without instrumental accompaniment. In the New Testament, musical offerings to God emanate from human hearts and proceed from human lips. This tradition is authorized by God via Jesus’s apostles and practiced in Scripture by the first Christians (Eph 5:18–19; Heb 13:15; see, e.g, Matt 26:30; Acts 16:25). The addition of mechanical instruments, however, started long after the church began and caused turmoil from the beginning. Some modern believers are more concerned than others about following the specific instructions and examples reflected in the New Testament, but to the extent believers desire to follow apostolic traditions, the musical praise believers offer in worship should emanate from their hearts and proceed from their lips without mechanical accompaniment.

[1] William T. Flynn, “Liturgical Music” in The Oxford History of Christian Worship, ed. Geoffrey Wainwright and Karen B. Westerfield Tucker (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2006) 771.